Выставка

Музей Альфонса Мухи — единственный в мире оригинальный музей, посвященный исключительно жизни и творчеству всемирно известного представителя стиля ар-нуво Альфонса Мухи (1860–1939 г.) — был открыт для публики в Праге 13 февраля 1998 года. В сентябре 2024 года экспозиция пополнилась новой коллекцией. В музее Мухи теперь представлены ключевые работы из знаменитой коллекции произведений Мухи Ивана Лендла, куратором которой является Джек Реннерт. Коллекция Ивана Лендла в настоящее время принадлежит инвестиционной компании Portu Gallery — члену WOOD&CO.

Экспозиция содержит плакаты парижского периода, а также ряд популярных коммерческих заказов для таких компаний, как, например, Moët & Chandon, Job Cigarettes и Lefèvre-Utile Biscuits.

Музей разделен на пять основных разделов:

- «Декоративные панно», «Парижские плакаты», «Рекламные объявления», «Чешские плакаты» и «Памятные вещи».

- Экспозиция завершается впечатляющим документальным фильмом о жизни и творчестве Альфонса Мухи.

- В экспозиции представлены наиболее значимые и популярные произведения плакатного искусства художника.

Раздел 1. Декоративные панно

Альфонс Муха был ведущим представителем стиля ар-нуво (модерн), требовавшего создания декоративной схемы, допускающей повторение стилистических узоров. Муха основывал свою работу на образе, который можно было организовать в несколько циклов, основанных на традиционных темах, как правило, взятых из физического мира. Поэтому Муха дал своему первому циклу декоративных панно, созданному в 1896 году, название «Времена года». Он продолжил эту практику, создав ряд весьма успешных панно, в которых соблюдается четырехкратная или двукратная вариация одной темы, в том числе «Четыре времени суток» (1899 г.) или «Драгоценные камни» (1900 г.) — работы того периода, когда стиль Мухи уже полностью сформировался. Стилизованное сочетание природы и красивых женщин было выражением его радостного представления о жизни, которое в то время очень ценилось в его кругу. С художественной точки зрения наиболее серьезным среди этих циклов можно считать цикл «Четыре искусства» (1898 г.), выполненный в нескольких техниках и особенно отличающийся поэтичностью замыслов Мухи. Последняя работа Мухи из представленных здесь панно — серия «Луна и звезды» (1902 г.). В данном случае фигуры скорее драматичны, чем чувственны по сравнению с другими циклами.

Цикл «Четыре искусства»

В своем цикле, воспевающем четыре жанра искусства, Муха сознательно не использует традиционные атрибуты, такие как перья птиц, музыкальные инструменты или кисти художника, а изображает каждое из искусств на фоне определенного времени суток: Танец — утро, Живопись — день, Поэзия — вечер, Музыка — ночь.

«Танец» из цикла «Четыре искусства» (1898 г.)

© Mucha Museum

«Четыре времени суток»

Четыре женские фигуры олицетворяют времена суток: каждая из них помещена в естественную среду в искусно оформленном обрамлении, напоминающем готическое окно.

«Утреннее пробуждение» из цикла «Четыре времени суток» (1899 г.)

© Mucha Museum

«Времена года»

Вышеупомянутая первая серия декоративных панно «Времена года» не была чем-то новым, поскольку графическое издательство «Шампенуа» уже реализовывало ее раньше с другими художниками. Однако Муха вдохнул в нее столько жизни, что этот набор декоративных панно стал одним из самых продаваемых.

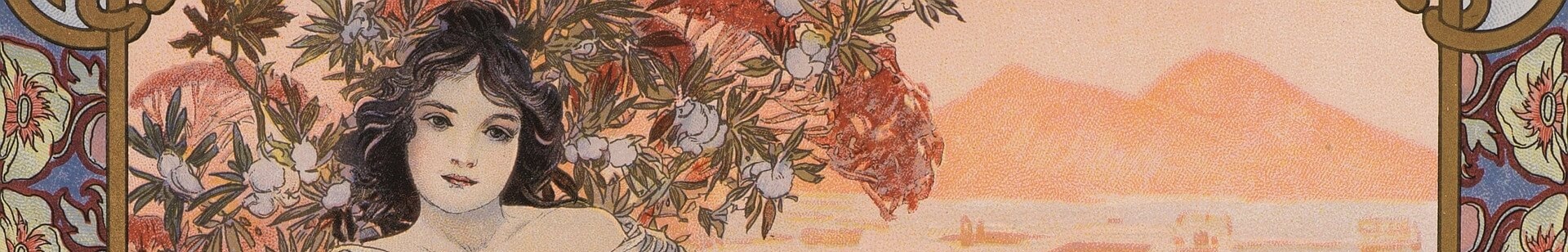

«Лето» из цикла «Времена года» (1896 г.)

© Mucha Museum

Раздел 2. Парижские плакаты

Плакаты, созданные в Париже в 1890-х годах, — наиболее известная во всем мире часть творческого наследия Мухи. Именно благодаря им он утвердил новый, свой собственный декоративный стиль. Основная группа состоит из плакатов, посвященных Саре Бернар, известной парижской актрисе. Первый из них, созданный на рубеже 1894 и 1895 г., изображал Бернар в главной роли Жисмонды. Сохранившиеся эскизы и печатные корректуры этого плаката демонстрируют через стилистическую и главным образом цветовую концепцию интенсивные поиски Мухой нового образа для плаката, несмотря на то короткое время, которое у него было на выполнение этого заказа. Его художественная революция принесла новую элегантность до сих пор пестрому «уличному салону», тем самым увеличив недавно обретенную значимость плаката для современного искусства. Однако плакаты с Бернар также содержат драматические тона, как, например, в «Медее» (1898 г.). Он также изображал ее в мужских ролях, например в пьесах «Лоренцаччо» (1896 г.) и «Гамлет» (1899 г.). Кроме того, на выставке представлены два варианта «Дамы с камелиями» — популярной пьесы о самопожертвовании ради любви. Последним парижским плакатом стал портрет Христа к пьесе «Страсти Христовы» (1904 г.). Все эти работы демонстрируют исключительную изобретательность Мухи и чувство визуально эффектной формы.

«Жисмонда»

Именно этот плакат принес Мухе известность. История его создания — легендарна, а многие комментаторы до сих пор ведут дискуссии о свойственных ему деталях. Нет сомнений в том, что сам Муха видел действие руки судьбы в обстоятельствах, которые привели его к созданию плаката.

Это событие произошло на Рождество 1894 года. Муха, любезно согласившись помочь другу, работал над корректурами в типографии Лемерсье, когда Сара Бернар позвонила туда со срочным заказом нового плаката для «Жисмонды». Все постоянные художники Лемерсье были в отпуске, поэтому он обратился к Мухе. Требование «божественной Сары» невозможно было игнорировать. Плакат, созданный Мухой, произвел революцию в своем жанре. Длинная узкая форма, нежные пастельные тона и неподвижность фигуры, выполненной почти в натуральную величину, придавали нотку достоинства и сдержанности, что вызывало поразительный эффект. Плакат был настолько популярен среди парижской публики, что некоторые коллекционеры подкупали расклейщиков плакатов, чтобы заполучить их, а другие даже срезали их с рекламных щитов по ночам.

Сара Бернар была в восторге от плаката и немедленно предложила Мухе шестилетний контракт на создание сценографии, костюмов и плакатов. В то же время художник подписал эксклюзивный контракт с графическим издательством «Шампенуа» на изготовление коммерческих и декоративных плакатов.

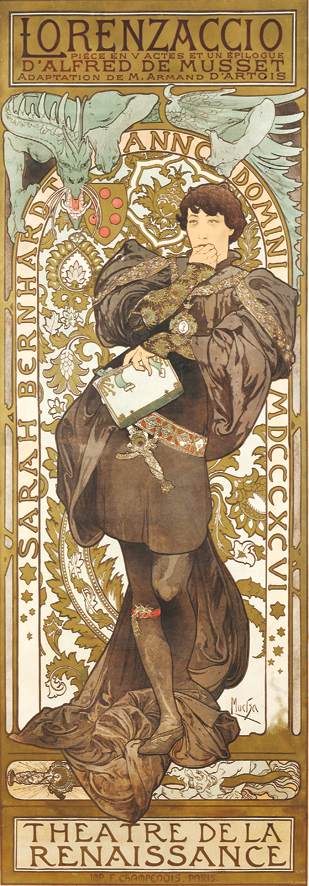

«Лоренцаччо»

В пьесе Альфреда де Мюссе «Лоренцаччо» Сара Бернар сыграла главную мужскую роль (Лоренцо Медичи) во время осады Флоренции тираном герцогом Александром, который на плакате символически изображен в виде дракона, угрожающего флорентийскому гербу. Лоренцо размышляет об убийстве Александра, что изображено в нижней части плаката.

«Жисмонда» (1894–1895 г.)

© Mucha Museum

«Лоренцаччо» (1896 г.)

© Mucha Museum

«Медея» (1898 г.)

© Mucha Museum

«Гамлет» (1899 г.)

© Mucha Museum

Médée

Драматург Катюль Мендес переработал классический текст Эврипида специально для Сары Бернар. Он изобразил греческого героя Ясона, который до этого времени воспринимался как неприкасаемый мифологический образ, как обманщика, предающего всех, кто любит его, в погоне за своими корыстными страстями, тем самым давая психологическое оправдание преступлениям Медеи. Суть трагедии полностью передана в одинокой фигуре на плакате. Мозаичный фон и использование греческой буквы «D» относят пьесу к античному периоду. Полный ужаса взгляд Медеи устремлен на сверкающий кинжал, зажатый в ее руке и залитый кровью ее детей, лежащих у ее ног. Внимания заслуживают необычайно детально изображенные руки, а также браслет из змеевика, украшающий предплечье Медеи. Этот браслет был задуман Мухой во время работы над плакатом, и Саре он настолько понравился, что она поручила ювелиру Жоржу Фуке создать для нее браслет и кольцо в виде змеи, инкрустированные драгоценными камнями, чтобы она могла носить их на сцене.

Hamlet

В пьесе Шекспира «Гамлет», которую для Сары Бернар перевели на французский Евжен Маран и Марсель Швоб, она сыграла главную мужскую роль. На заднем плане за центральной фигурой Гамлета виден призрак его убитого отца, бредущий по стене Эльсинора. Утонувшая Офелия лежит в цветах у ног Гамлета. «Гамлет» стал последней афишей, созданной Мухой для Сары Бернар.

Раздел 3. Рекламные объявления

Коммерческая деятельность Альфонса Мухи сыграла центральную роль в его славе, особенно его плакаты с товарами и брендами времен Прекрасной эпохи. Прорыв произошел в 1894 году с созданием вышеупомянутого плаката «Жисмонда» для актрисы Сары Бернар, после которого появились заказы от таких крупных компаний, как Moët & Chandon, Job Cigarettes и Lefèvre-Utile Biscuits. Самым впечатляющим плакатом в этом разделе является заказ для Nestlé — «Дань уважения Nestlé» (1897 г.) — подарок королеве Виктории в честь ее 60-летия. На плакатах Мухи были изображены изящные, стройные женские фигуры в окружении цветочных мотивов и плавных линий, олицетворяющих стиль ар-нуво. Его проекты подняли повседневные товары на новый уровень и сделали их синонимом красоты и роскоши. Помимо рекламы продукции, его коммерческие заказы также включают плакаты для таких событий, как Всемирная выставка 1900 года в Париже, Бруклинская выставка 1920 года или плакат Монако — Монте-Карло, призывающий парижан посетить залив. Благодаря литографии эти работы стали производиться массово. Сочетая в себе изобразительное искусство и рекламу, они сформировали современные маркетинговые тенденции.

«Зодиак»

Один из самых популярных плакатов Мухи, «Зодиак», изначально был выпущен графическим издательством «Шампенуа» как фирменный календарь 1897 года. Однако он так понравился главному редактору журнала La Plume, что он купил права на его распространение в качестве их календаря на тот же год. Известно как минимум 9 вариантов «Зодиака», включая представленный здесь, который был напечатан без какого-либо сопроводительного текста и использовался в качестве декоративного панно.

«Зодиак» (1896 г.)

© Mucha Museum

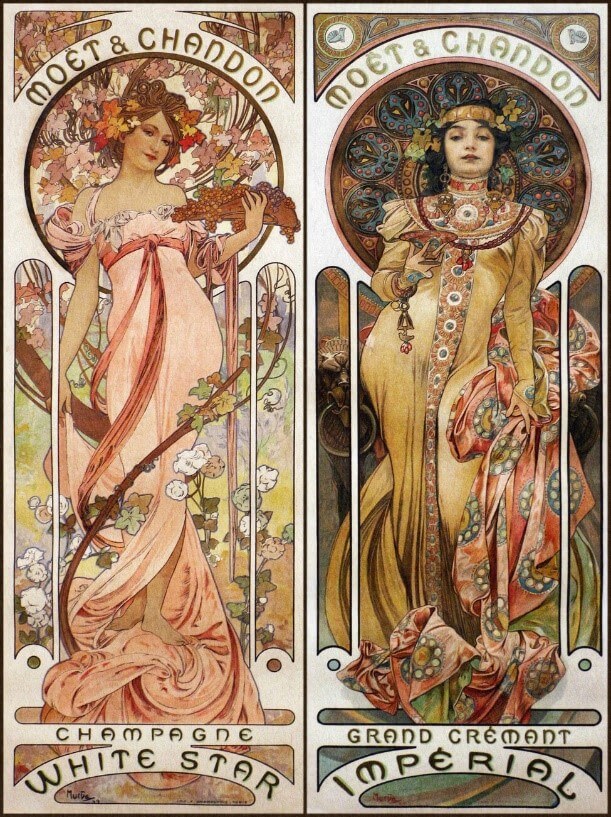

Moët & Chandon

Муха разработал ряд дизайнов для компании Moët & Chandon, которые использовались в меню, открытках и других рекламных материалах. Два его заказа представляли собой плакаты: один использовался для рекламы белого шампанского, а другой — для рекламы вина Dry Impérial.

Moët & Chandon (1899 г.)

© Mucha Museum

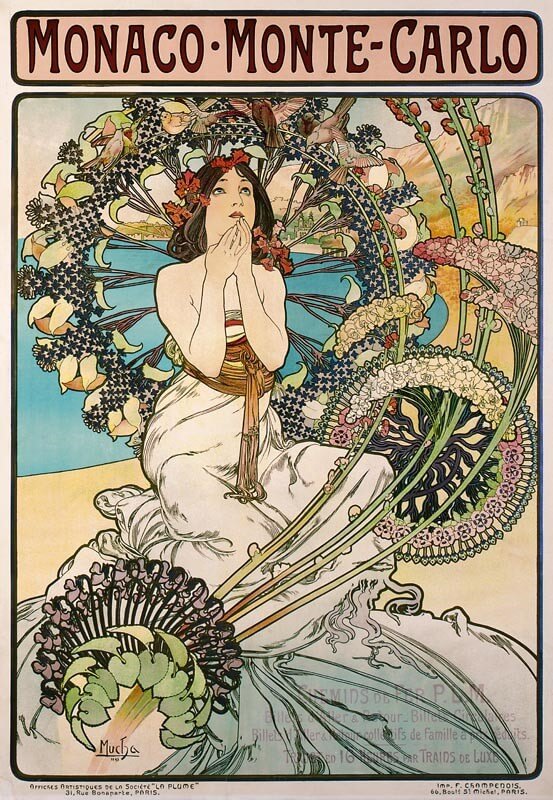

«Монако — Монте-Карло»

Эта работа Мухи отличается роскошным дизайном. Застенчивая девушка, стоящая на коленях и восхищенная спокойствием залива Монте-Карло, полностью окружена изгибающимися стеблями сирени и гортензии, представляющими собой одни из самых замысловатых соцветий, когда-либо написанных Мухой. Поскольку заказчиком была железнодорожная компания Chemin de Fer P.L.M., вполне вероятно, что дизайн должен был вызвать ассоциации с рельсами и колесами, благодаря которым люди добираются до Монте-Карло.

«Монако — Монте-Карло» (1897 г.)

© Mucha Museum

Раздел 4. Чешские плакаты

Вернувшись в 1910 году на родину, Альфонс Муха смог, наконец, удовлетворить свое сокровенное желание всецело обратиться к своему народу, чтобы средствами искусства выражать его потребности и идеалы. Таким образом постепенно сформировался новый цикл афиш, художественно отличающихся от парижских. В тематическом плане мы встречаем главным образом по-новому раскрытый фольклорный мотив, подчеркивающий цветовую красочность моравских костюмов и нежный тип славянских девушек, представленных здесь «Хоровым обществом моравских учителей» (1911 г.). Контракт для банка взаимного страхования «Славия» (1907 г.) в Праге Муха получил еще во время пребывания в США. Есть также плакат к его самому монументальному произведению — «Славянской эпопее» (1928 г.), который словно вырезан из куска работы «Присяга чешского общества Омладина под славянской липой». Завершаем этот раздел лирическим воспоминанием о парижских мотивах в произведении «Принцесса Гиацинт» (1911 г.).

«Принцесса Гиацинт»

Афиша «Принцесса Гиацинт» рекламирует одноименную балетную пантомиму Ладислава Новака и Оскара Недбала с популярной актрисой Андулой Седлачковой в главной роли. Мотив гиацинта здесь неоднократно повторяется. Он представлен на вышитом платье, на эффектных серебряных украшениях, а также на символическом круге в руке принцессы.

«Принцесса Гиацинт» (1911 г.)

© Mucha Museum

«Хоровое общество моравских учителей»

«Хоровое общество моравских учителей» было хоровым коллективом, в репертуаре которого была представлена классическая, популярная и народная музыка, в том числе песни композитора Леоша Яначека. Хор гастролировал по Чехии, а также по всей Европе и США. В качестве внимательного слушателя на плакате изображена молодая женщина в народном костюме из Кийовской области. Ее персонаж напоминает декоративное панно «Музыка» из цикла «Четыре искусства».

«Хоровое общество моравских учителей» (1911 г.)

© Mucha Museum

Раздел 5. Памятные вещи

В этом разделе экспозиции у вас будет возможность увидеть небольшие работы Мухи. Альфонс Муха разработал серию марок, банкнот и других национальных символов для вновь образованной Чехословакии после Первой мировой войны. Будучи гордым патриотом, Муха проявлял глубокую приверженность культурной и политической самобытности своей родины. Дизайн чехословацких почтовых марок его авторства, который датируется 1918 годом, стал его вкладом в становление страны как независимого государства после распада Австро-Венгерской империи. Банкноты, дизайн которых Мухе было поручено разработать в 1919 году, отличались фирменным стилем Мухи: орнаментальными, плавными линиями и мотивами, отражающими национальную идентичность. Среди других экспонатов, представленных здесь, — иллюстрированная молитва «Отче наш», а также личные письма и открытки.

Дизайн витража для собора Святого Вита в Праге (1900 г.)

© Mucha Museum

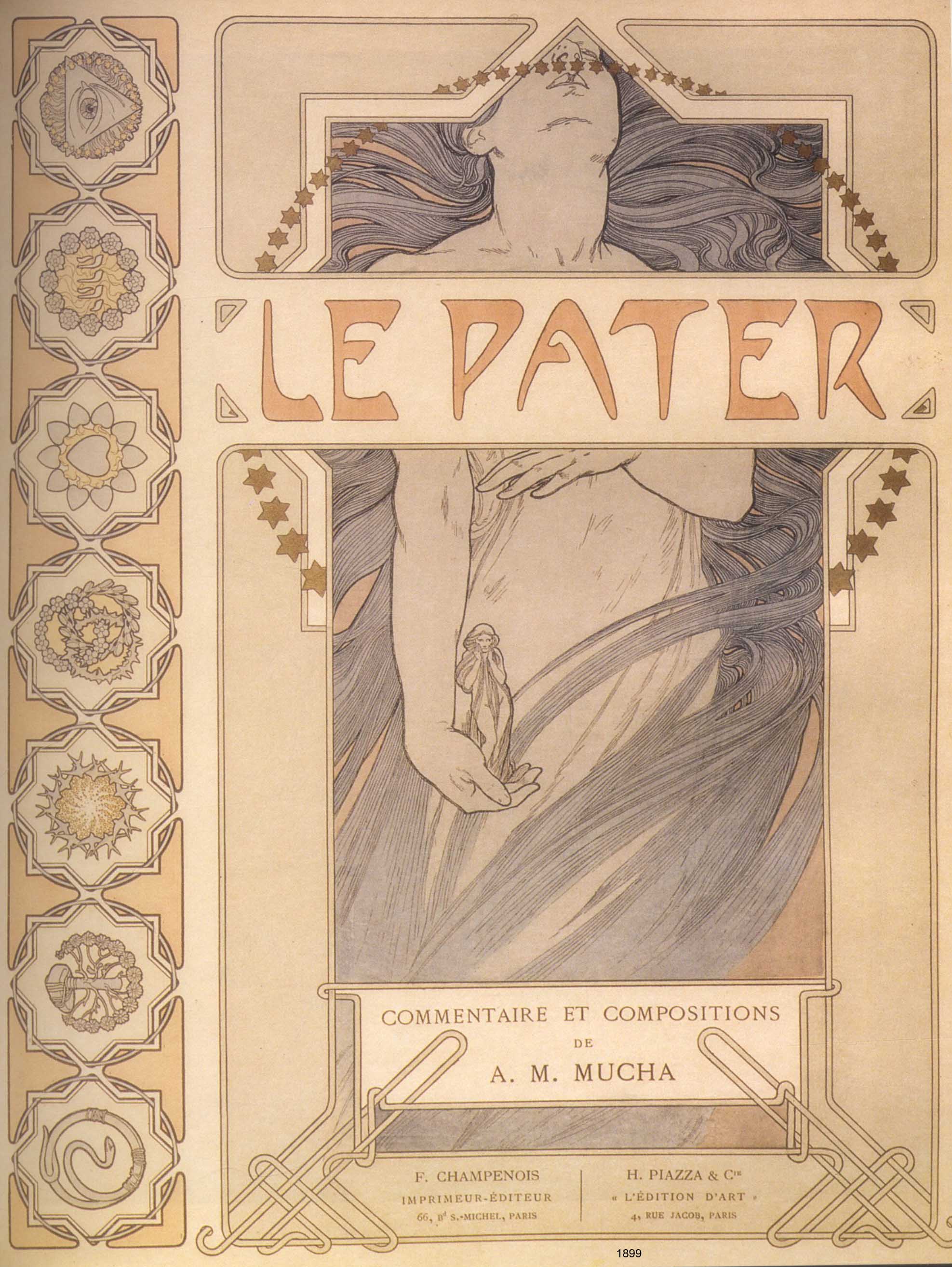

«Отче наш» – титульный лист и пять последующих страниц

Муха считал «Отче наш» одним из своих лучших произведений. Эти иллюстрации были напечатаны в Париже тиражом в 510 пронумерованных экземпляров (390 — на французском языке и 120 — на чешском) Анри Пьяццей, которому Муха посвятил это произведение.

Муха писал о работе «Отче наш» следующее: «Тогда я видел свой путь в другом месте, на порядок выше. Я искал способ распространить свет, который бы достигал даже самых отдаленных уголков. Мне не пришлось долго искать. Отче наш. Почему бы не придать этим словам графическое выражение?»

В «Отче наш» Муха разделяет молитву на семь стихов. Он анализирует каждый стих на трех декоративных страницах. На первой странице Муха представляет стих на латыни и французском языке, окруженный декоративной композицией, включающей геометрические и символические мотивы. На второй странице представлен комментарий Мухи к содержанию стиха, подражающий средневековым иллюминированным рукописям в цветовом оформлении буквицы (заглавной буквы). На третьей странице представлена монохромная интерпретация стиха Мухой. Эти фантастические иллюстрации представляют борьбу человека на пути от тьмы к свету.

«Отче наш» (1899 г.)

© Mucha Museum